The winding road takes us through lush woodland to a mountain lake and up to an open landscape where the blue sky contrasts with the green vegetation and craggy mountains. The clanking of bells echo in the stillness as our first greeting comes from a flock of wooly sheep. They scamper toward us, friendly and energetic. Happy to receive our hands stroking their smooth faces. We climb over a fence and take a moment to let it all sink in. A small and idyllic cottage faces the morning sun and is surrounded by small, wooden buildings. Metal milk cans decorate the walls and summer blossoms add a pop of color against the green and brown backdrop.

The winding road takes us through lush woodland to a mountain lake and up to an open landscape where the blue sky contrasts with the green vegetation and craggy mountains. The clanking of bells echo in the stillness as our first greeting comes from a flock of wooly sheep. They scamper toward us, friendly and energetic. Happy to receive our hands stroking their smooth faces. We climb over a fence and take a moment to let it all sink in. A small and idyllic cottage faces the morning sun and is surrounded by small, wooden buildings. Metal milk cans decorate the walls and summer blossoms add a pop of color against the green and brown backdrop.

There’s no internet access. No distractions. Nothing to take you away from the majesty and quietness of the landscape expect for a small radio, a good book and a thoughtful conversation. This is a place which blends itself into the nature. Learns from it, protects it, nurtures it and hails it. It is here I find myself today. A seter. A Norwegian seter. Slettastølen Seter, to be exact.

There’s no internet access. No distractions. Nothing to take you away from the majesty and quietness of the landscape expect for a small radio, a good book and a thoughtful conversation. This is a place which blends itself into the nature. Learns from it, protects it, nurtures it and hails it. It is here I find myself today. A seter. A Norwegian seter. Slettastølen Seter, to be exact.

This is possibly the most quintessential Norwegian farm experience. The seter, or sœter, is a mountain farm used during the summer season; a settlement of buildings which emerged to utilize grazing areas that were not suitable for year-round habitation. It is an integral part of Norwegian agriculture, with an emphasis on milk production from cows and goats. The practice of summer farming is said to be as old as farming in Norway. Archaeological finds have traced summer farming to the Iron Age, in the 7th century. Why the seter method began in Norway is unclear, yet theories suggest that as farms expanded, it became more difficult for animals to return during the evenings, therefore they created specific farming areas for the summer months. Summer farming was regulated in the laws that were set in the 12th century. According to the Gulatingslova (old Norwegian law) if a farmer did not herd his animals to the summer pasture, he could be reported for illegal grazing, or ‘grass robbery’. (Source)

In older times, cows produced two-thirds of their annual milk production during the summer farming period, which could then be turned into food products that could be stored and used during the long winter months. This was a vital process to the country of Norway because of the harsh winters. In the 1800s, there were close to 50,000 mountain farms in operation throughout Norway, with most farms having one or more seter with a part of the population of the villages spending the entire summer on the seter with the animals. Today, there are around 1,000 mountain farms in operation. In addition, 800 farms herded their animals to shared summer farms. This means that around 15-20,000 goats and 35-40,000 cows in Norway spend their summers happily grazing and being milked at the pastures. Even more non-producing cattle, sheep and lambs graze in the area, contributing to a cultivated landscape and the maintenance of biological diversity. (Source)

As the summer months bring quality, fresh milk, this is when many speciality Norwegian cheeses are created, such as brunost, prim, surost & gamalost, to name a few.

As the summer months bring quality, fresh milk, this is when many speciality Norwegian cheeses are created, such as brunost, prim, surost & gamalost, to name a few.

Small scale processing on the seter is a treasured art form. The skill and labor involved to create so many traditional and unique products is not as easy to come by these days. The knowledge and expertise to care for the animals and create a variety of products is invaluable and important to sustaining this type of farming. Our lovely and generous hostess for the day, Sonja, and her family are just some of the key players in maintaining this important lifestyle.

Sonja greets us with a warm smile as she welcomes us to Slettastølen. Her daughter, Solfrid, is helping her today. Soon, Sonja’s mother, Agnes Gloria, arrives to meet us as well and join us for lunch. Sonja proudly shows us around the seter. She has a small area for milk production. In one of the adjoining rooms, she has a takke, a wood-fired griddle, with an old copper pot on top, as large and as wide as the takke itself. It is here she uses traditional methods to prepare her prim, a spreadable brown cheese made from cooking down cream and whey. She also shows me an old milk separator and a waffle iron, rusty and worn with years of good use.

Sonja greets us with a warm smile as she welcomes us to Slettastølen. Her daughter, Solfrid, is helping her today. Soon, Sonja’s mother, Agnes Gloria, arrives to meet us as well and join us for lunch. Sonja proudly shows us around the seter. She has a small area for milk production. In one of the adjoining rooms, she has a takke, a wood-fired griddle, with an old copper pot on top, as large and as wide as the takke itself. It is here she uses traditional methods to prepare her prim, a spreadable brown cheese made from cooking down cream and whey. She also shows me an old milk separator and a waffle iron, rusty and worn with years of good use.

Sonja leads us around to the barn and we meet one of her cows. The cows provide her with a steady supply of fresh milk, which she utilizes to make her quality, homemade dairy products. She takes us inside the cottage. It’s a working cottage. Practical, substantial, and welcoming. With cheery curtains, wooden baskets, heat coming from the fireplace and fruit and flowers adorning the nooks and crannies, the cottage is koselig. It acts as home during the summer months with everything one would need to get by. A small sink in the entryway for washing up, wood for the fireplace, a table and chairs, a couple of beds and a gas stove.

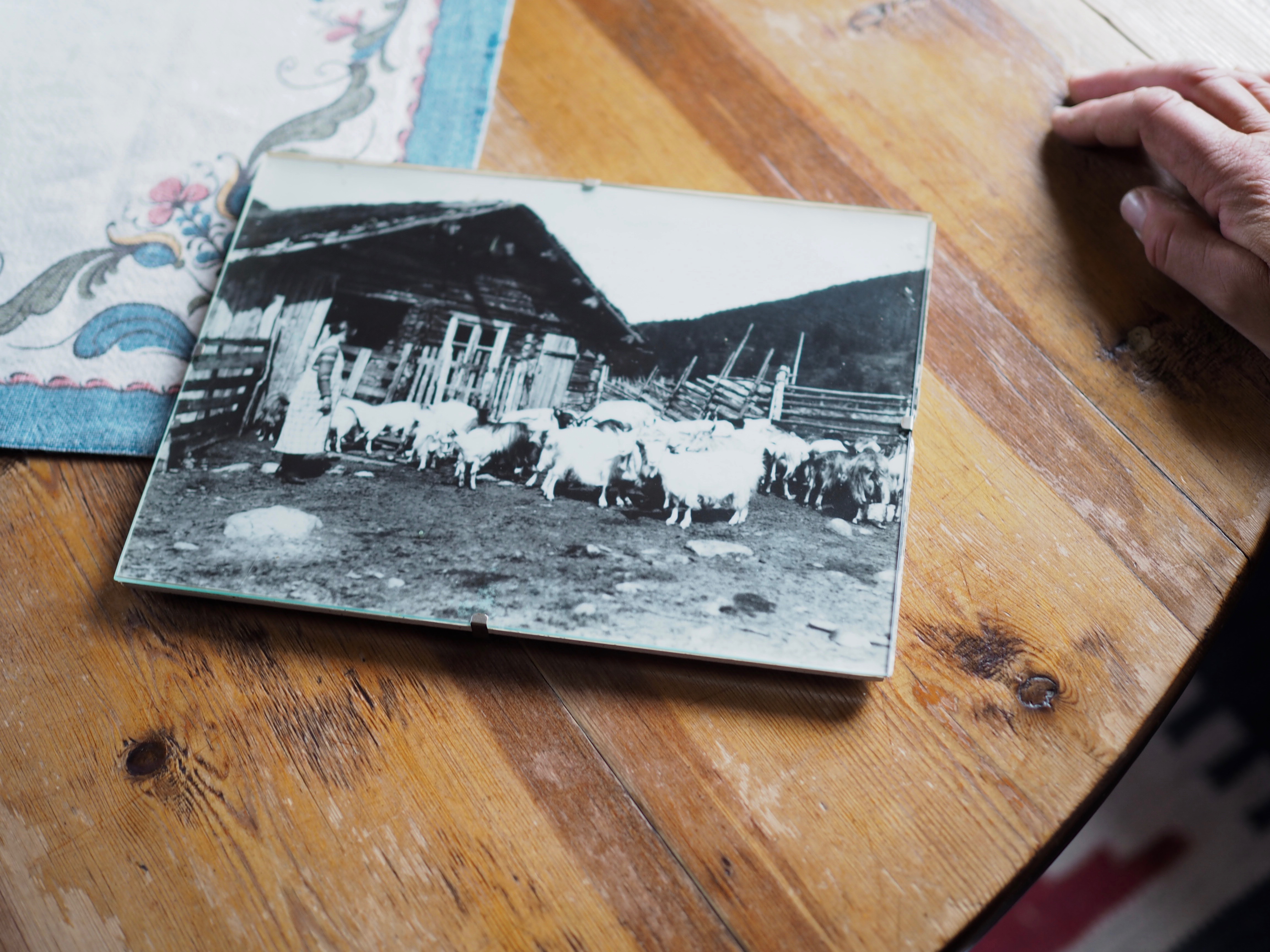

Sonja reaches for two black and white pictures handing on the wall. Each show the farm generations ago. She tells us the stories that make up the seter’s history as it traces back to the 1800s. She shows us the rooms and explains how the shepherd’s quarters once lined up against a horse’s stable at the front of the cottage. Now, the two rooms have been opened up to include a sitting area, fireplace and couple of beds. The main area, where we are now, includes the kitchen, dining area and a few more beds. But not long ago, this cottage looked slightly different, housed many more and yet remained the same size it is today. When Sonja was little, she would stay in one part of the cottage with her aunt and family while the other part was rented out to ‘city folk’ looking for an authentic farm adventure.

Sonja reaches for two black and white pictures handing on the wall. Each show the farm generations ago. She tells us the stories that make up the seter’s history as it traces back to the 1800s. She shows us the rooms and explains how the shepherd’s quarters once lined up against a horse’s stable at the front of the cottage. Now, the two rooms have been opened up to include a sitting area, fireplace and couple of beds. The main area, where we are now, includes the kitchen, dining area and a few more beds. But not long ago, this cottage looked slightly different, housed many more and yet remained the same size it is today. When Sonja was little, she would stay in one part of the cottage with her aunt and family while the other part was rented out to ‘city folk’ looking for an authentic farm adventure.

Understandably, it is clear to see what is so attractive about the seter life. It’s idyllic. Fresh, mountain air, stunning and open landscape, animals grazing freely, and a quietness, which is not always so easy to come by in our busy lives. It’s relaxing and yet evokes a desire to work. The labor of the seter is no easy task, but it seems inviting. Doable. A worthy challenge because the rewards are so great, so tangible.

Understandably, it is clear to see what is so attractive about the seter life. It’s idyllic. Fresh, mountain air, stunning and open landscape, animals grazing freely, and a quietness, which is not always so easy to come by in our busy lives. It’s relaxing and yet evokes a desire to work. The labor of the seter is no easy task, but it seems inviting. Doable. A worthy challenge because the rewards are so great, so tangible.

Sonja places a tub of homemade ost (cheese) on the table. I can’t wait to try it. In fact, other than seeing the seter and meeting Sonja, my main reason for coming is to watch her make her cottage cheese. But this is a treat. A wonderful surprise. I suppose the clock says it’s nearly noon, but the excitement has made me loose track of time completely. We might have a bite of cheese with some rolls, but Sonja has other ideas. She turns on the gas stove and places a pot on top and fills its with her homemade sour cream. Shall I make rømmegrøt? She asks, yet it is more of a statement than a question. Sofrid assumes her position in front of the pot and begins to whisk, a hefty job which takes some time. Sonja continues to fill the table with what seems like an endless supply of delicacies. Cottage cheese (sur-ost), sour cream (rømme), prim, kneeding cheese (knåost/trøgost), cooked cheese (kokeost), cloudberry jam, strawberry jam, rhubarb jam, whole milk, butter, and fenelår, all of which she has made. And finally, the rømmegrøt is placed on the table, smooth and creamy. A seter feast. A triumphant meal highlighting some of the best products Sonja makes from her animals and the landscape. She is a true artisan.

It’s hard to know where to begin. But Sonja becomes our guide and we start with a bowl of rømmegrøt with sugar and cinnamon sprinkled on top with a spoonful or two of the fat which has separated from the sour cream while it cooked. It’s heaven. Rømmegrøt made from store-bought sour cream tastes nothing like the slightly tangy and delicate version Sonja makes. It’s a testament to the cow’s milk and to Sonja making it from scratch.

It’s hard to know where to begin. But Sonja becomes our guide and we start with a bowl of rømmegrøt with sugar and cinnamon sprinkled on top with a spoonful or two of the fat which has separated from the sour cream while it cooked. It’s heaven. Rømmegrøt made from store-bought sour cream tastes nothing like the slightly tangy and delicate version Sonja makes. It’s a testament to the cow’s milk and to Sonja making it from scratch.

Next, Sonja teaches me about Ystingsoll. It’s the name of the dish when you mix together surost (cottage cheese), rømme (sour cream), whole milk and prim. This recipe hails from the mountainous regions of Norway, presumably Numedal and Hallingdal. It’s a special setermat, or farm food. It has a tangy, sweet and creamy taste which I can’t quite put my finger on, but it’s good. I finish my bowl. Every last spoonful.

We end the afternoon learning to make surost, a farm cheese made from soured milk. With a handful of leftovers to take home, we say our goodbyes and wave to the seter as we drive off through the picturesque landscape with full bellies, wide grins and the sun hitting our faces.

We end the afternoon learning to make surost, a farm cheese made from soured milk. With a handful of leftovers to take home, we say our goodbyes and wave to the seter as we drive off through the picturesque landscape with full bellies, wide grins and the sun hitting our faces.

Tusen takk to our lovely hostesses, Sonja, Solfrid and Gloria Agnes for inviting us to take part in a proper seter experience and for feeding us endless quantities of delightful delicacies! And to my dear friend, Ingrid, for organising and coming along! ♥

Sonja’s recipe for Rømmegrøt

Sonja’s recipe for Surost / Farm Cheese

[…] visit to Slettastølen Seter introduced me to the Norwegian Seter Life, or mountain farm life. Sonja treated me to a banquet of […]

This is so beautiful it almost makes me cry, pulling at all the nostalgic strings and ways of life that seem to be slipping away.

Thanks Naomi! I love these stories and the people who continue to keep the old traditions going. Not to mention, there is so much we can learn when we step away from the busyness of life.

Hi,

Was wondering where this farm is? Would definitely love to visit as a Chef, gastronome:)

Hi, Sonja’s farm is located in Nore and Uvdal and is not generally open to the public. However, you can easily find a seter/setær that is open to the public across various parts of Norway during the summer 🙂

How does a frabod compare with your Mt Farm story?

Hi Cindy, I’m not familiar with a frabod – can you explain?

I absolutely loved reading this blog and the accompanying photos. Was reading a novel by Lauraine Snelling of a turn of the century family from Norway farming in Minnesota. ?? “Seter” on google and was led to your site. My lifelong dream is to visit Norway & Sweden!

Thank you, Mariette! I hope you’ll get a chance to visit soon 🙂